Effects of the Introduction of Colour on the Aesthetics of German and British Music Television

A contribution by Sven Boxberg and Lily Hußmann

Introduction

Few of the turning points in recent media history seem as incisive and instantaneous at the same time as the switch from black and white to colour television. TV was black and white and then it wasn’t – or so it goes. In other words, popular television history tends to paint a picture of a clear before and after, a pre and post colour. In reality the switch to colour was of course neither instantaneous nor did it happen simultaneously across the globe. Rather, between pre and post colour there lies the transitional period that is the 1970s, a decade undeniably fraught with socio-economic changes on a massive scale that often found their expression in popcultural phenomena. In this article we interrogate one such phenomenon that happened to coincide with the rise of colour TV: British glam rock. In contrasting glam with the (mostly) black and white television career of the Beatles we trace the before and after, but also the in-between of colour television.

Bearing in mind the excessive visual styles of glam artists such as David Bowie, T. Rex or Roxy Music, it is easy to draw parallels between these aesthetic developments and the introduction of colour TV in Britain. Indeed, the link between the two has long been regarded as fact by scholars such as Philip Auslander (2006), Ian Inglis (2011), Ian Chapman and Henry Johnson (2016), and most recently Jon Stratton (2022), and is therefore very well documented. German music television of the 1970s is another story. Literature on this period of German music television is scarce in general and most authors discuss the switch to colour in passing, if at all (e.g. Heinze and Krull 2022; Siegfried 2016). There is also the question of availability. It was much more feasible for us to visit the archives of the ZDF and WDR than the BBC, which is the reason why this article examines Radio Bremen’s Beat Club (1965–1972) and its successor Musikladen (1972–1984), as well as the ZDF-competitor disco (1971–1982), and compares their visual aesthetics to those of their British counterparts Top of the Pops (1964–2006) and Old Grey Whistle Test (1971–1983). Since we wanted to compare performances of a glam artist who had ideally appeared on all of the above, we settled on T. Rex, who did indeed appear everywhere except the Old Grey Whistle Test (which may be significant in and of itself when it comes to questions of authenticity). We are aware of the white-male bias of glam historicisation and would like to take the liberty to point out Katharina Alexi’s (2021) article on female glam artists, as well as Auslander’s chapter on Suzi Quatro (2006, 193–226), that seek to remedy this issue. We decided to go with T. Rex as a case study here simply because we needed a certain amount of material to analyse.

The article is structured into a pre-colour section, a transition section, and a post-colour section. We begin by taking a look at the music television landscape pre-colour and the Beatles as an example of black and white TV stardom. Subsequently, the transitional period is discussed in relation to the Beatles film Magical Mystery Tour (1967). Finally, we delve into the phenomenon of T. Rexstasy and trace the development of their performance style across several performances on German national TV.

Pre-Colour: “Baby’s in Black” (and White)

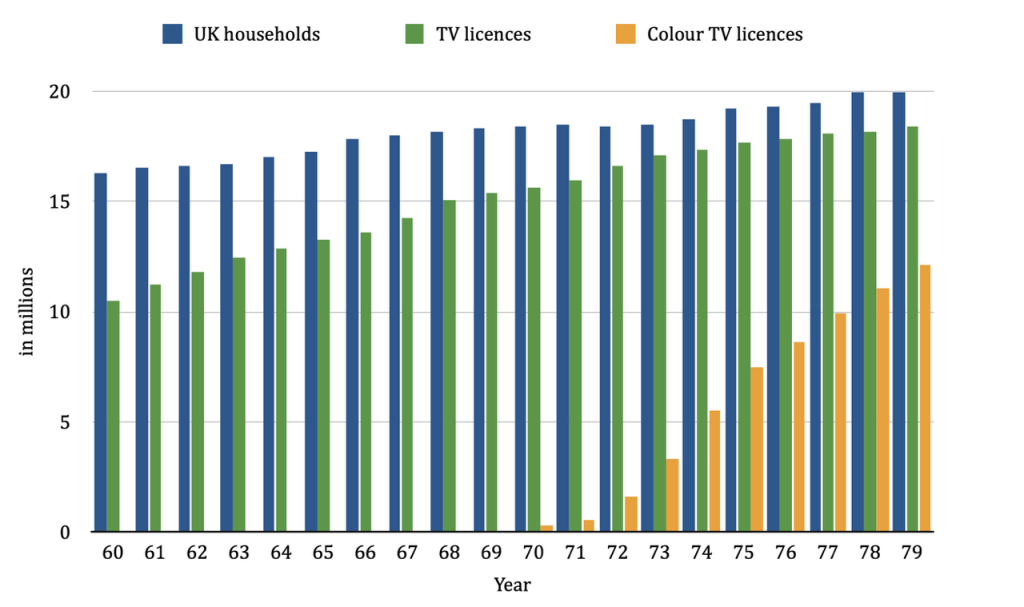

On September 1st, 1939, the BBC turned off its television transmission which would not return until June 1946. Though television did not immediately become a central medium after its rebirth after the war, its adolescence and maturity coincided with the rise of British pop stars. In 1947, approximately 15,000 households in the UK had a television set (cf. Fig. 1). By the time of the British Invasion in 1964 it would be almost 13 million (BBC 1986, 161). There are curious parallels between the artists that were born during and shortly after World War II and the medium that came to play a most prominent part in their eventual stardom. One of the questions that inevitably arises is how these aspects correlate, how the mass media of television and music interacted with and shaped each other. The Beatles are an obvious (if over-researched) example of early television stardom. The band was at the core of a musical revolution that swept not only across the UK and the US, but seemingly the whole world, enabled through their multimedial omnipresence.

The Beatles’ appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show on February 9, 1964, is undoubtedly central to their immense exposure, as was their first TV appearance in the UK. However, the sheer quantity of their international TV appearances during their early days also contributed massively to their rise to near universal fame. All of them, obviously, were in black and white, and so was their first film A Hard Day’s Night in 1964. Even some of their early albums were released with monochrome pictures of the band members only.

While the audience saw all of their favourite musicians mainly in black and white unless they went to the movie theatre, engineers were steadily working on matching one of the unique selling points that cinema had over TV. Even though the technical prerequisites were already available, colour television was not yet economically viable. This applied to German TV as well as to British. While not every country in Europe experienced an economic boom in the sixties, television was a phenomenon that spread in a variety of countries in a similar way. By the end of the decade, a majority of people in the UK (around 84%) and Germany (68%) had access to a TV in their household (Hickethier and Hoff 1998, 201).

With regards to music television, both countries were practically forced to broadcast shows by popular demand. The switch from acts being part of a programme (like the variety shows where several acts appeared with short sets) to bands being the main focus, happened gradually over the course of the sixties. Beat Club, produced by Radio Bremen, was one of the earliest dedicated music programmes and the most successful music show in Europe between 1967 and 1969. It is noteworthy that its production quality was generally highly regarded:

Among critics and in professional music circles, Leckebusch was widely admired as being at the vanguard of what a TV producer could do. When The Who appeared on the Beat-Club, their manager Kit Lambert wrote to Leckebusch, “That was a great television you did on the Who. We were all knocked out” (Siegfried, 257).

From the get-go, German music television was heavily UK-influenced, as British musicians still had an elevated position representing a dominant role in popular culture. Up until the end of the decade, Beat Club had British presenters alongside ones hailing from Germany. The change in direction to a more psychedelic presentation with more avantgarde video-techniques coincided with the change from playback to more live performances and also the transition to colour.

“Transition / Transmission”

By 1967, the BBC was broadcasting some programmes in colour, however the transition period to widespread colour TV adoption went well into the 1970s. While some aspects of music television worked regardless of colour, it was clear that colour was the next evolutionary step. Which brings us back to the Beatles, who produced their film Magical Mystery Tour, which was a TV special, in colour in late 1967. However, its initial broadcast in black and white was not effective in conveying the vibrant and multicoloured visuals that were supposed to match the psychedelic music and artistic concept.

The interrelation between the colourful reality and its mediation to audiences is a complicated issue that is increasingly hard to understand as we move further away in time. A comparable evolutionary development in our lifetime could be the transition from low resolution small CRT TVs to large high resolution flat screens resulting in more quality TV productions, or the tendency to consume more content on portable devices, which can be correlated with the rise of short-form media. The adoption rate was and still is tied to economic questions, as colour TVs were quite expensive in the beginning and as with all new technology, economy of scale took some time to take effect.

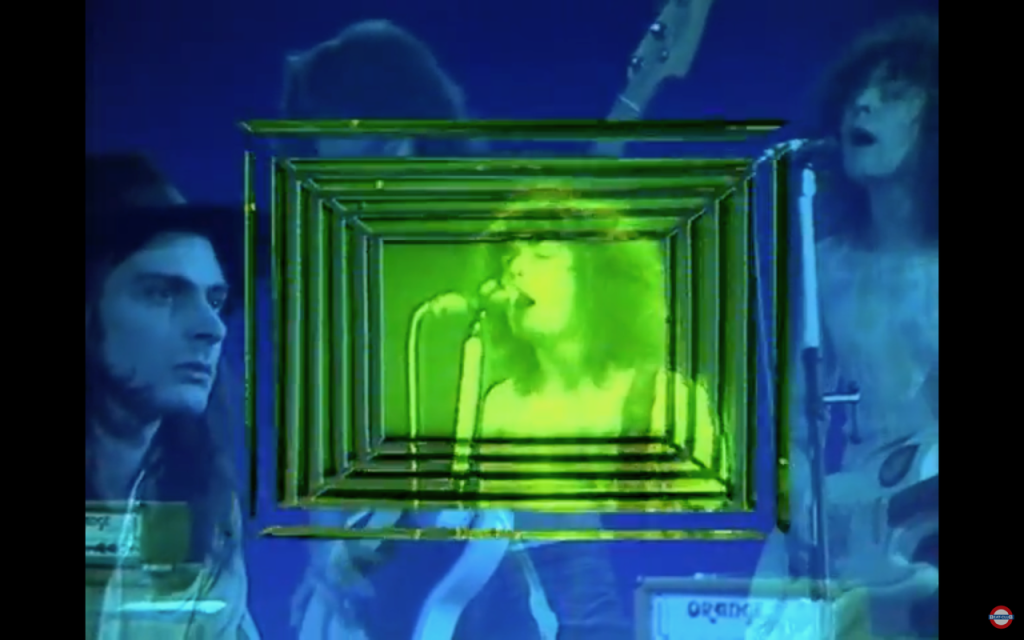

So the need for backward compatibility resulted in programmes being produced with both colour and monochrome viewers in mind. Chromakeying and other effects were quite prominent even when the broadcast itself was still without colour. Also, a kind of “meta” use of TVs was a recurring trope in disco. Here we can see that the TVs used on their set were still black and white in 1971.

Not only were the production techniques “glamorous” regardless of colour, but also independent of the band. In our research we found that the technicians and camera operators had considerable creative freedom and their individual artistic handwriting was present in the way the effects were used.

As we can see, glamorous and campy outfits were already a staple of late 60s fashion. See the difference in The Who’s style between 1965 (Fig. 3) and 1968,

as well as the Beatles in 1967 next to their 1964 waxwork counterparts (Fig. 4). If any correlation is to be observed, the desire for colourful outfits to be transmitted accurately predates the widespread representation of such colourful fashion on TV. However, it is plausible that with the growing availability of colour TVs, there was a positive feedback loop that increased the demand and desire for it.

Post-Colour: “Oh man, I need a TV when I’ve got T. Rex!”

By the time colour television was widely adopted in British households in the mid-70s, the Beatles had broken up and another musical mass phenomenon had emerged. “T. Rexstasy”, and Glam Rock mania in general, were in large parts mediated by television. T. Rex’s career was kickstarted and further facilitated by television appearances, to the point that by 1972, “T. Rexstasy” was being hailed as “the new Beatlemania” (Auslander 2006, 71) – and they were more than willing to fill the popcultural gap left in the wake of the Beatles’ breakup. Alongside David Bowie, T. Rex can be considered the main proponents of the first generation of Glam Rockers and initiators of the genre. Their music, like Bowie’s, had a strong visual element and was characterised by a foregrounding of performative aspects – not least the performativity of gender –, which played into the fact that Britain had by now become a consumer society that commodified not only music itself, but also the artists who produced and performed it. The rise of TV advertising can be cited as a central influence here (Stratton 2022, 84–87; 96–108).

Unlike some countercultural rock groups like Led Zeppelin, who refused to appear on Top of the Pops for fear of losing credibility with their audience, Glam Rockers deliberately leaned into the artificiality of mimed TV performances, as evinced by more than a dozen Top of the Pops appearances by T. Rex alone. Marc Bolan’s ties with television were further strengthened in 1977 when he got his own television show where he mimed old T. Rex hits and hosted rock, pop and early punk acts. The Marc Show largely depended on the cult of personality he had built up as T. Rex frontman, though, and had a limited budget, ending abruptly with his death by car crash on September 16th of the same year after only six episodes.

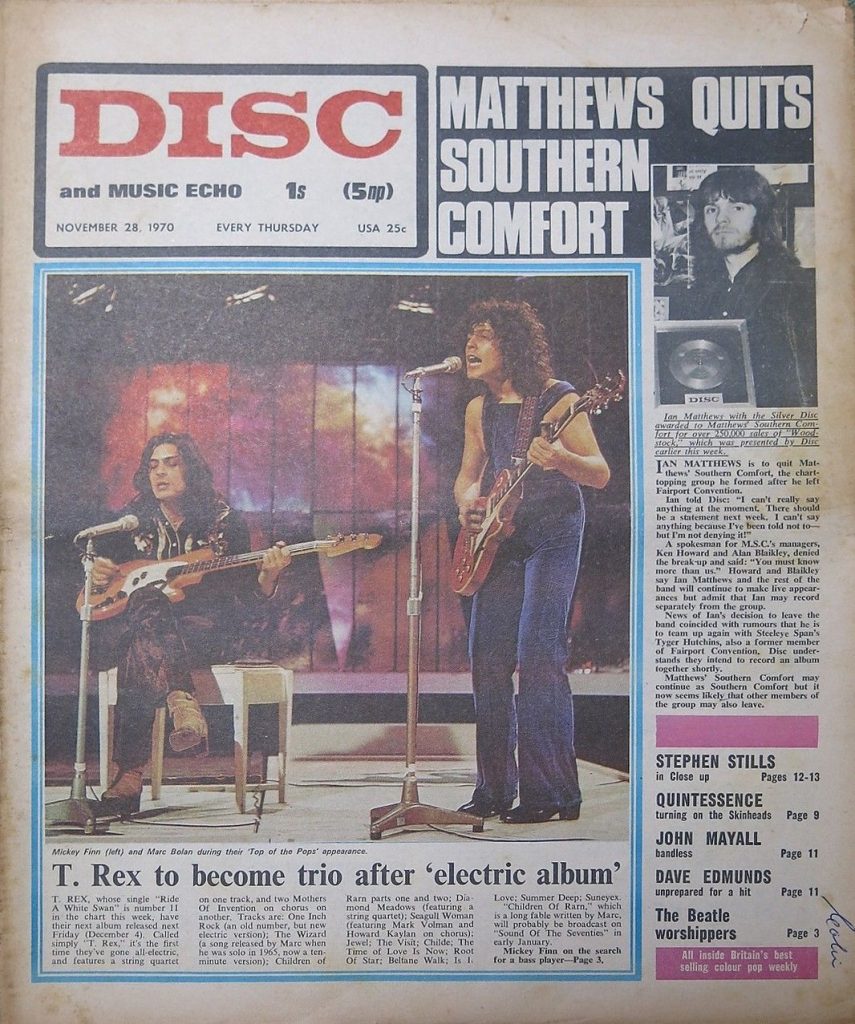

A handful of performances from T. Rex’s early years are going to illustrate how the frontman “transformed from Bolan the hippie minstrel of Tyrannosaurus Rex to Bolan the androgynous Glam Rocker of T. Rex as he entered the televisual colour spectacle” (Stratton 2022, 95). While Bolan became an excessive, larger than life version of himself, T. Rex’s music tended to be relatively straightforward. From 1970 onwards, their songs are usually short, formally and harmonically simple with singable melodies and a danceable beat cushioned by producer Tony Visconti’s string arrangements. Other than that, their sound was characterised by heavily distorted electric guitar, acoustic guitar, congas, high male backing vocals and Bolan’s recognisable singing style, alternating between an effeminately soft vibrato and aggressively masculine shouting. The lyrics are seemingly apolitical, focusing on themes of love, dancing, and mild space-age-psychedelia, as well as objects of consumer desire, particularly cars. To oversimplify: T. Rex’s music is informed by 1950s rock’n’roll, updated to the sonic possibilities of the 1970s, but, most importantly, visually and vocally queered – which was only now becoming safely possible in Britain due to the Decriminalisation of Homosexuality Act of 1967. Although the question as to what constitutes a “queer voice” cannot be answered here in all its complexity, there is certainly a development to be observed in the sound of Bolan’s voice throughout their performances. In any case, their music was absolutely political. T. Rex first appeared on Top of the Pops in late 1970 with their first commercially successful single, Ride a White Swan, which reached number two on the UK singles chart in January the following year. Footage of this performance is unavailable, but a surviving image firmly roots them in a hippie aesthetic, as do other photos from this time (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). They also performed this track live on Beat Club on the 27th of February, 1971, along with the track Jewel. To fully understand the creative decisions here, it is necessary to view the performance in context of their early career. T. Rex emerged from London’s underground scene, and were initially a hippie-esque acoustic duo operating as Tyrannosaurus Rex, but they were going electric for their new album after Bolan had replaced his previous percussionist with Mickey Finn and shortened their name. Accordingly, Beat Club treated them to the same effects they would usually apply to psychedelic rock groups.

T. Rex first appeared on Top of the Pops in late 1970 with their first commercially successful single, Ride a White Swan, which reached number two on the UK singles chart in January the following year. Footage of this performance is unavailable, but a surviving image firmly roots them in a hippie aesthetic, as do other photos from this time (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). They also performed this track live on Beat Club on the 27th of February, 1971, along with the track Jewel. To fully understand the creative decisions here, it is necessary to view the performance in context of their early career. T. Rex emerged from London’s underground scene, and were initially a hippie-esque acoustic duo operating as Tyrannosaurus Rex, but they were going electric for their new album after Bolan had replaced his previous percussionist with Mickey Finn and shortened their name. Accordingly, Beat Club treated them to the same effects they would usually apply to psychedelic rock groups.

The visual effects here are fairly disorienting and create an impossible spatiality by placing simultaneous musical moments side by side and on top of each other. The far away, dream-like quality of the performance is supported by the sound, which features a generous wash of reverb on the vocals and guitar that is absent from the studio recording. While the musicians’ faces are shown looking off into the middle distance, the use of chroma key prohibits the viewer from making out many details, and there isn’t a single naturally coloured shot. We argue, a bit counterintuitively perhaps, that the excessive use of effects here actually indicates a primacy of the “music itself” over the visual aspects of the performance. By diverting attention from the performing bodies, the audience are encouraged to employ a contemplative mode of listening compliant with countercultural ideas of musical aesthetics, such as authenticity and sincerity of expression. Further, improvised solo passages are highlighted as moments of musical significance, reinforcing notions of the importance of instrumental virtuosity and spontaneity. This is particularly evident from the ending jam of Jewel, where the visual effects reach their climax in an overwhelming swirl of colours while the musicians improvise.

While these stylistic decisions must have seemed appropriate at the time, they feel incongruous with later T. Rex performances, such as this Musikladen live performance of 20th Century Boy on the 21st of February, 1973. Here, the camerawork strives to foreground Bolan’s physical presence, and to establish an intense connection to the television audience via extreme close-ups of his eyes and face looking and pointing directly at the camera. The cuts here are just as aggressive as the heavily distorted guitar riff. There are no visual effects at all, save for a kind of slow motion effect to highlight the guitar solo at the end and a final overlay of Bolan’s eyes staring down the viewer.

In the same vein, their mimed performance of Jeepster on disco on the 15th of January, 1972, makes do without any visual effects, focussing mainly on Bolan’s energetic performance, which by then had become increasingly formulaic, mixing and matching gestures from the physical vocabularies of Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Eddie Cochran and the like, but also closer contemporaries such as The Who’s Pete Townshend. It is clear that the music takes the backseat here in favour of the bodies both on and off-stage, since the whole performance is also interspersed with shots of the dancing studio audience.

In this respect, disco differs from the later Beat Club and its successor Musikladen; the former did away with the studio audience in mid-1969, the latter never included one. From the way the shows were conceived, one could argue that disco was simply a German version of the commercial Top of the Pops, while Beat Club and Musikladen sought to emulate the more alternative Old Grey Whistle Test, where artists played live without exception and were chosen regardless of their commercial success. And while the programming was certainly heavily influenced by and reliant on its British counterpart, this line of argument would be overly reductionistic, as it deprives disco of its rather unique position in the German music television landscape of the time, which disco host Ilja Richter describes as tripartite:

[…] links der „Beat-Club“, rechts die „Hitparade“, „Disco“ in der Mitte. „Beat-Club“ brachte die wüstesten Sachen von Zappa bis zu den Doors, und Uschi Nerke trug dazu Miniröcke von aufsehenerregender Kürze. Über die „Hitparade“ gebot Dieter Thomas Heck […]. Er gab sich ganz dem deutschen Schlager hin. Und „Disco“ brachte beides. Deutschen Schlager und englischsprachigen Pop (Richter 2001, 110).

It further distinguished itself via the frequent incorporation of sketches – of, at times, dubious quality –, like this T. Rex parody from 1973, which displays a uniquely German (and working class) engagement with the lyrics of their song Metal Guru.

Finally, we can credit disco with a certain degree of self-awareness evident in the studio design, which foregrounded television technology and did very little to disguise the show’s production. On the contrary, it revelled in it and nearly fetishised the technology involved. The act of “Rüberschalten”, of switching over to Top of the Pops, was in itself ritualised and performed by Richter from a brightly coloured “moderation station” that included various studio monitors and buttons as well as a telephone (cf. Fig. 7). For transitions, the camera would often zoom into one such monitor, and viewers would pass through the black and white screen and end up at the colourful BBC through TV-magic.

Conclusion

To return to the initial question of the relation between colour television and the rise of glam rock, we first of all have to keep in mind that there is no such thing as a clear pre and post colour. The dichotomy might seem clear-cut from our contemporary viewpoint due to the way we tend to compartmentalise the past, however, the transition period went on for a considerable time. Historicisation is a process that happens inadvertently, and in a visual medium such as television the switch from monochrome to colourful is one of the most incisive switches imaginable. Even though the culture of colour was already present in the sixties, it arguably became even more “real” and accessible when one of the leading visual media began to transmit it more accurately.

Incidentally, this transitional period coincided with an ideological shift in the dominant music culture that can be traced through both British and German music television. Glam turned away from countercultural notions of what music and musicians should be like: authentic in their expression, androgynous in a peace-and-love, but ultimately cis-heteronormative way, focussed on “the music itself” rather than its commercial success. Instead, Glam Rockers embraced the artificiality that came with mainstream television success. And while popular music had been a commodity for the longest time, by taking on excessive performance personae as they entered the “televisual colour spectacle” (Stratton 2022, 95) Glam Rockers willingly participated in their own commodification, which to us seems like the inevitable next step at that stage of capitalist consumer society (see also Beregow 2017). Considering that colour television was able to more accurately “represent reality”, embracing the unreal and excessive seems only logical. For T. Rex and Marc Bolan in particular, crossing into the colour-televisual space coincided with a shift in sound, visual style and vocal persona that could partly be attributed to the switch to colour, or rather: to the implications of becoming a colourful object of consumer desire on the small screen. However, to confirm this connection on a broader scale a more systematic investigation may be necessary.

With regards to the specificity of German music TV formats, we found that while Beat Club was the only internationally successful format, it was so not because of its Germanness but despite it. Its unique selling point was that it presented Anglo-American pop music in its own enticing visual aesthetic that was technologically miles ahead of Top of the Pops and Old Grey Whistle Test at the time. disco, on the other hand, was initially a Top of the Pops copy, but came to occupy a unique position between English pop and German Schlager, further distinguishing itself through Richter’s sketches that often displayed a specifically German view on this music. The aforementioned ideological shift can be observed in German music TV insofar as the more countercultural Beat Club had to make way for more conventional formats such as disco and Musikladen.

In conclusion, colour TV alone did not initiate the rise of Glam rock, but undoubtedly played a part in its expansion. Certainly, the influence German music TV had on a predominantly British music phenomenon such as Glam Rock should not be blown out of proportion, but its importance as a medium that allowed German audiences to gain access to this music is undeniable and absolutely deserves further study.

About the Authors

Lily Hußmann (*2000, they/them) hat von 2019 bis 2024 an der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Musikwissenschaft/Sound Studies und Anglistik studiert und mit einer Arbeit zu Autosongs in britischem Cock Rock das Studium abgeschlossen. Derzeit studiert Lily im Master Musikwissenschaft an der Universität zu Köln und arbeitet als WHB am Cologne Systematic Musicology Lab. Interessensschwerpunkte liegen in queerfeministischen Perspektiven auf populäre Musik und Medien.

Sven Boxberg (*1996, er/ihm) hat an der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Musikwissenschaft/Sound Studies und Anglistik studiert und hat 2024 seinen Master in Musik- und Klangkulturen der Moderne mit einer Arbeit zu Popmusik im Vietnamkriegsfilm abgeschlossen. Seine Forschungsinteressen sind Filmmusik und Popkultur.

References

Books and Articles

Alexi, Katharina. 2021. “Glam ‘Heroines’. Gaps in Glam Historicisation from Black Self-Feminised Musicians… to the Herstory of Glam Rock.” Studia de Cultura 13 (2): 7–20.

Auslander, Philip. 2006. Performing Glam Rock. Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music. University of Michigan Press.

Beregow, Elena. 2017. “Glam.” In: Handbuch Popkultur, edited by Thomas Hecken and Marcus Kleiner. J. B. Metzler.

British Broadcasting Corporation. 1986. BBC Annual Report and Handbook 1987.

Chapman, Ian, and Henry Johnson. 2016. Global Glam. Style and Spectacle from the 1970s to 2000s. Routledge.

Hann, Michael. 2016. “Jimmy Page: ‘Led Zeppelin weren’t gonna fit on Top of the Pops’.” The Guardian, September 20. https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2016/sep/20/jimmy-page-interview-led-zeppelin-complete-bbc-sessions.

Heinze, Carsten, and Dennis Krull. 2022. “Zwischen Subversion, Klamauk und Anpassung. Pop- und Rockmusik im westdeutschen Fernsehen der 1960er bis 1980er Jahre.” In Jugend, Musik und Film, edited by Kathrin Dreckmann et al. düsseldorf university press.

Hickethier, Knut, and Peter Hoff. 1998. Geschichte des deutschen Fernsehens. J.B. Metzler.

Inglis, Ian. 2010. Popular Music and Television in Britain. Ashgate.

Led Zeppelin Official Website. “Shows: March 27, 1969”. Accessed April 29, 2025. https://www.ledzeppelin.com/show/beat-club-TV-march-27-1969.

Murray, Susan. 2018. Bright Signals. A History of Color Television. Duke University Press. Richter, Ilja. [1999] 2001. Meine Story. dtv.

Siegfried, Detlef. 2016. “Pop on TV. The national and international success of Radio Bremen’s Beat Club.” In Perspectives on German Popular Music, edited by Michael Ahlers and Christoph Jacke. Routledge.

Stratton, Jon. 2022. Spectacle, Fashion and the Dancing Experience in Britain, 1960–1990. Palgrave Macmillan.

Videos

disco 4. 1971. Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen, June 5. Posted by Radio.Lux on 29.12.2019. YouTube, 42:37. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QZLNhjuO2fQ&list=PLASwqFh7oXe5eft0ZOK2xURo9B_qOou1T&index=3.

T. Rex. 1971. “Jewel.” Beat Club 64, Radio Bremen and Westdeutscher Rundfunk, February 27. Posted August 17, 2020, by Beat-Club. YouTube, 5:03. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LAVkRlX96Os.

T. Rex. 1971. “Ride a White Swan.” Beat Club 64, Radio Bremen and Westdeutscher Rundfunk, February 27. Posted March 1, 2013, by Beat-Club. YouTube, 2:31. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lGJm91719Ik.

T. Rex. 1972. “Jeepster.” disco 11, Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen, January 15. Posted September 16, 2013, by fritz51177. YouTube, 4:09. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bxzRJmMcfc8.

T. Rex. 1973. “20th Century Boy.” Musikladen 3, Radio Bremen, February 21. Posted February 6, 2019, by Musikladen. YouTube, 3:57. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9SG65dlho_o.

The Who. [1968] 1996. “The Who, Michael Lindsay-Hogg – A Quick One (While He’s Away).” Posted November 19, 2019, by TheWho. YouTube, 7:36. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJv2-_–EY4.

Photographs

Cooper, Michael. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band Album Cover. 30.03.1967.

de Telloer, Philippe. The Who in 1965. 1965.

Disc and Music Echo, “Mickey Finn (left) and Marc Bolan during their ‘Top of the Pops’ appearance.” 28.11.1970.

Wentzell, Barrie. Marc Bolan on Hampstead Heath with Gibson Les Paul. May 1970.

Schreibe einen Kommentar

Du musst angemeldet sein, um einen Kommentar abzugeben.